The Cat is the Key

To reconcile Meaning and the Many

I am both a dog and a cat person, maybe more of a dog one though, but for all intents and purposes, within this second installment of Talking Too Many, I am a cat person, because that's the key to fully grasping a brand as something more than a marketing entity, as a multifaceted, polymorphous, constantly evolving, cultural one. Don't you worry, I'll start to get less amorphous and ethereal in the third installment of Talking Too Many - coming within a month from now I hope - to entertain this thought: "The Creators are The Brand".

Mind the gap between brand signs and brand meaning

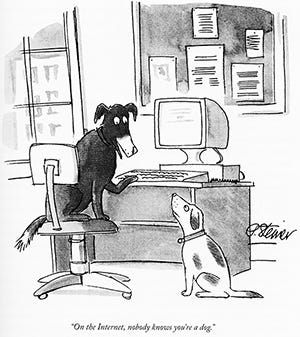

On the Internet nobody knows if you’re a dog, and cats are ubiquitous. Although the former only have happenstance to thank for their digital related popularity1, the latter may have ended up here out of serendipity, for a reason that might not be apparent at first, but that eventually makes sense when it is revealed. Cats were already present in the first myths that were laid in writing for us to witness and remember; they were the protectors of pharaohs in ancient Egypt, cast in stone as statues representing deities, buried with what this civilization held as most sacred and precious, eternalized in the hieroglyphs that for so long had eluded our comprehension. In other words cats made up for great story characters. They were the extraneousness, the oddity in the story, the bridge between what we know, cats as we see them, and what we cannot fathom still, cats as we see them behaving. A cat is an odd being indeed; it goes crazy at night when the dark is finally deep enough that you won’t detect its next move; it appears out of the blue to startle you ever so softly; it walks a fine line like nothing else, only to stumble and make a mockery of itself. A cat captures the gap between what’s perceived and what’s meant, between the signifier and the signified. Therefore in the cat rests one of the most profound issues there’s ever been for mankind to ponder; in this gap resides everything that we experience without ever completely understanding it: can this be real? To quote Claude Lévi-Strauss “The mana, the manitou, the thing, the gizmo is nothing else than the imperfect connection between signifier and signified, a gap between what always precedes, the signifier, which has been fully given since the beginning of times, and what follows, the signified.”2 The thing with cats is that they are both the observed experience and the unattainable meaning, they are within our reach yet so hard to catch, they are true to our eyes yet false to our cognition. Cats may not belong to the world of myths anymore, but they certainly are more art than science, just like our representations of reality. Staying with Claude Lévi-Stauss a little longer, we can say that “art inserts itself at equal distance from scientific knowledge and mythical or magical thought.”3 When science explores the formal characteristics of matter or the human mind, when mythical thought makes sense of the world from felt experiences, art itself proceeds from the vast diversity of the world all the while producing artefacts that are immediately recognizable and apprehensible by the great many of us.

There’s a wide gap between what we see and experience, artefacts such as videos, soundbites, quotes, posts or pics, and the profusion of matter, information and knowledge available all around us, such as the billions of hours of videos produced every day on earth. It is in that gap that we should approach brand strategy, in a space where information is sent over wavelengths or stored in clouds, news spreads fast before it backfires, memes are made so idiosyncratically and shared so universally, images created to reveal our selves and our shelves, posts tell nothing to say it all. Our sphere of communication goes round and round, it won't stop so that we may step back and grasp it in full, we are always part thereof, never able to offer a complete, detached and unbiased view of what it is to watch, talk and share in a rolling feed of information. This is but the fate of our human experience after all, stuck as we are between two Kantian worlds, that of beauty, where everything exists in the moment, where nothing exists outside the eyes and the intellect of any one person, where no overarching concept prevails, on the one hand, and the world of logic on the other, where mathematical, physical, environmental and cosmic truths abound without much concern for human judgment. Billions of us see, and all form worlds within themselves, assigning different meanings to shared experiences. Billions of us would see in the past, but that was it. Now not only do we see by the billions, we talk by the billions, which we'd never been used to, and therein lies the source of our discomfort with the XXI century in respect of information, communication, culture, cognition - and yes, brand strategy.

The world is complex, so should the world of brands be

Our experienced realities are, to a great extent, so much different from those of the past. Up until the invention of writing very few people had the power to share information or change minds. Stories told in oral ages either had very small audiences, inside villages or tribes, or would travel in time, from generation to generation, to become collective poems, norms or myths. The origins of the Iliad and the Odyssey are still being debated, as the singular body of works of one poet named Homer, or as the collective works of generations of Greek aezi who would speak these stories from the second millennium BC4 before they were codified in a comprehensive body of works in the first millenium BC. As individuals could not travel far in space nor in time, they had to invent stories that could gradually shape minds and societies. Even though handwriting and papyruses helped spread the Word, humanity had to wait until the XV and XVI centuries, and the advent of the printing press, to see a clear increase in the ability to share information at speed with larger audiences, an ability that was mostly reserved to monarchs and heads of state at first, before becoming available to many private publishers, whether with business or political agendas, in the XVIII and XIX centuries. This is where we stood in the XX century, and this is where our considerations, reflections and reflexes still linger, in a gap that still felt comprehensible, even though quantum theories and the concept of entanglement had already started telling a different story:

We think of the world in terms of objects, things, entities (in physics, we call them "physical systems"): a photon, a cat, a stone, a clock, a tree, a boy, a village, a rainbow, a planet, a cluster of galaxies ... These do not exist in splendid isolation. On the contrary, they do nothing but continuously act upon each other. To understand nature, we must focus on these interactions rather than on isolated objects. A cat listens to the ticking of a clock; a boy throws a stone; the stone moves the air through which it flies, hits another stone and moves that, presses into the ground where it lands; a tree absorbs energy from the sun's rays, produces the oxygen that the villagers breathe while watching the stars, and the stars run through the galaxies, pulled by the gravity of other stars... The world that we observe is continuously interacting. It is a dense web of interactions.

- Carlo Rovelli in Helgoland

Our shared realities are hard to pin down, they always have been, probably because they reside in that gap, the one that bridges our observations and every other possible interpretation or explanation for a given phenomenon or behind a beholden artefact. With the acceleration of time and the associated abridgment of space, with the preternatural (sic) ability to reach the farthest reaches of earth in no time, with the new possibilities of intervention afforded to the many, that gap has become both wider and deeper. Our shared realities are far more plural, diverse, diluted and distributed than they used to be even though the phenomena or objects we gaze upon look pretty similar. A video, a segment of news, a publication, an interview, a portrait, they all look the same as yesterday, yet they hover above an inscrutable abyss, one that feels impossible to fathom, one where concepts like fake news, conspiracies, dark patterns, ghosting, shadow banning, algorithmic bias or doxing proliferate. In that new reality made by the many, in that ever widening gap where realities now collide, there are compasses we can use, provided we know how to recalibrate them. There are ways in which we can still make sense of that gap, in which we can reconcile meaning and the many.

Culture is the brand playbook, not just its playground

Most marketing and brand strategies still rely on canonical concepts from communication and business theories established in the XX century, in a world that was complicated but not complex, one where there was a pretty linear and predictable path between the source of a message and its intended recipients, with very limited entropy along the way. To put it more simply a brand only had to do a few sequential things to be seen and heard: define a few single-minded messages, weave them into advertising campaigns or PR talking points, run them on some of the few existing media and attention gatekeepers (print, radio, TV, OOH, retail), expect consumers to act upon those. I know this sounds simplistic, and to be sure a lot of thinking and crafting had to be injected, but the overall picture was simple enough to wrap your head around.

As attention comes in shorter bursts and on smaller screens, as content is measured daily in billions of creators and hours, as sly algorithms dictate what gets seen and amplified, the 4 Ps of marketing - Product, Price, Place, Promotion - are no longer enough to define and express oneself, to stand out, acquire and retain consumers. The marketing funnel is not enough. A brand platform is not enough. Yes they matter greatly, and I thoroughly enjoy designing them in canonical or disruptive5 ways.

In a world gone social, brands have to look beyond the marketing playbook and use frameworks and tools that will make them into cultural objects. Culture is not to be construed in a narrow way here, one that is usually reserved for artists, literature, music or films for instance. Culture is to be apprehended in its anthropological way, as the total frame that defines and binds human societies together, with four dimensions: Relations (through Language, Families and Trade), Art, Science & Religion.

These four dimensions are the sum total of what is needed to create culture, to form societies. As evidenced by the evolution of branding and marketing vernacular in the past 20 years (for better or worse), with branded content, entertainment, experiences, installations or communities, we must understand that the branding playbook has to be culture encompassing and not squarely marketing based.

To be sure over the past 10 to 20 years we have been "implementing" brand strategies through more avenues and channels than the ones inherited from the XX century. But, beyond a few exceptions like DTCs, have we really been taking into account early on the relations we strive to build within communities and around commerce? Are we incorporating in our strategic vision the consumers and creators we will write and tell our stories with? Are we willing to keep our brand strategies in constant beta as we gather in-vivo behavioral data from our users that may contradict the initial in-vitro assumptions we made? Do we see interfaces as the artefacts that will primarily define our brands? This is what I mean by seeing brands as ecosystems: they're made of much more than targets and statements, they're alive, they're multifaceted, they're made of particles that certainly collide and maybe collude to define the brand. The following is one way to think about everything 😶🌫️ we must bring into the fold of a brand strategy, and not just its implementation.

Let us take time to explore that gap where meaning by the many resides and eludes us, let us treat brands just like we see cats, accepting that the signifier comes before the signified, and that we will spend a lifetime contemplating, tweaking and caring for them.

Just as the individual is not alone in the group, nor any one society alone among the others, so man is not alone in the universe. When the spectrum or rainbow of human cultures has finally sunk into the void created by our frenzy; as long as we continue to exist and there is a world, that tenuous arch linking us to the inaccessible will still remain, to show us the opposite course to that leading to enslavement; man may be unable to follow it, but its contemplation affords him the only privilege of which he can make himself worthy; that of arresting the process, of controlling the impulse which forces him to block up the cracks in the wall of necessity one by one and to complete his work at the same time as he shuts himself up within his prison; this is a privilege coveted by every society, whatever its beliefs, its political system or its level of civilization; a privilege to which it attaches its leisure, its pleasure, its peace of mind and its freedom; the possibility, vital for life, of unhitching, which consists - Oh! fond farewell to savages and explorations! - in grasping, during the brief intervals in which our species can bring itself to interrupt its hive-like activity, the essence of what it was and continues to be, below the threshold of thought and over and above society: in the contemplation of a mineral more beautiful than all our creations; in the scent that can be smelled at the heart of a lily and is more imbued with learning than all our books; or in the brief glance, heavy with patience, serenity and mutual forgiveness, that, through some involuntary understanding, one can sometimes exchange with a cat.

- Claude Lévi-Strauss in Tristes Tropiques

”On the Internet nobody knows if you’re a dog” is a maxim and meme about digital anonymity first published in The New Yorker on July 5, 1993 as a cartoon and caption by Peter Steiner.

LEVI-STRAUSS Claude, Introduction à l’œuvre de Marcel Mauss, translated by the author from French to English.

LEVI-STRAUSS Claude, La pensée sauvage, translated by the author from French to English.

Before the Greek Dark Ages, the period of Greek history from the end of the Mycenaean palatial civilization around 1100 BC to the beginning of Archaic age around 750 BC.

Disruption® is the trademark - in all senses of the term - philosophy and methodology of TBWA.